In Stanley v. Sanford, a 7-2 majority made possible by the three Trump justices narrowed the protections of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Specifically, the Court limited the ability of people with disabilities to sue their former employers for discrimination in providing post-employment benefits. Justices Sotomayor and Jackson dissented.

What was this case about?

Karyn Stanley was a firefighter in the city of Sanford, Florida. When she was hired, the city included several fringe benefits in addition to her salary. They included a subsidy for retirees to cover their health insurance up to age 65. This benefit was available to people who retired after 25 years of service, or who retired early due to disability.

But a few years after Stanley was hired, the city changed its policy. Retirees with 25 years of service remained eligible for the health insurance benefit until they were 65. But people who retired due to disability remained eligible only until they received Medicare benefits or two years after retirement, whichever comes first.

Stanley developed Parkinson’s disease and had to retire early on disability at the age of 47. She lost the health insurance subsidy after just two years, rather than having it continue until age 65.

What was the issue before the Court?

Stanley sued the city for violating her rights under the ADA. The lower court ruled that she did not fit the ADA’s definition of a “qualified individual” covered by the law.

Under Title I of the ADA, employers may not discriminate against “a qualified individual” on the basis of their disability. The ADA defines a qualified individual as someone who “can perform the essential functions of the employment position that such individual holds or desires.” This case involves a former employee with a disability who alleges that limits on her retirement benefits violate the ADA. The question for the Court was whether a former employee is a “qualified individual” under the ADA, since she no longer holds or even wants a job with the employer. This question had divided lower courts.

How did the majority rule, and how does it hurt people?

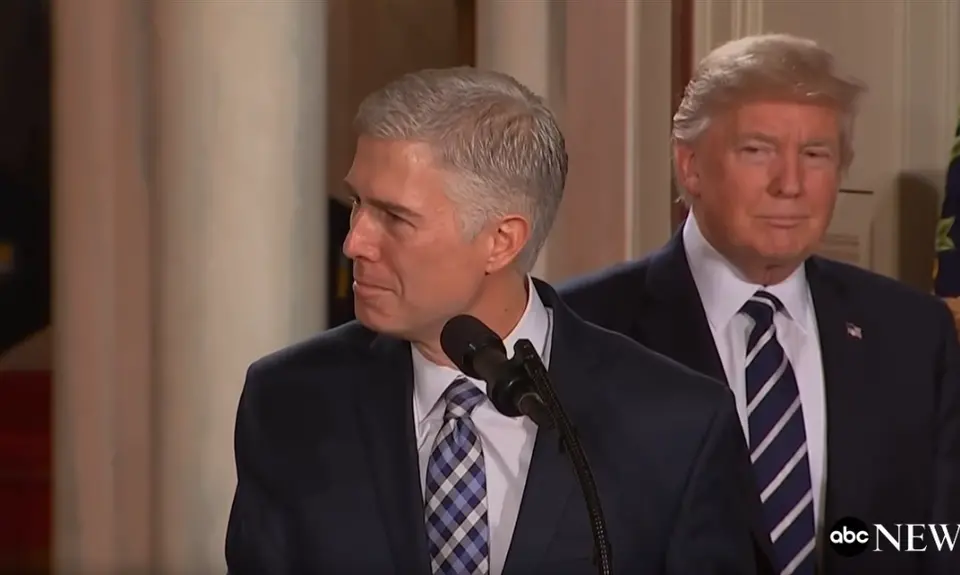

In a 7-2 decision written by Justice Gorsuch and which the other two Trump justices joined, the Court ruled against the former employee in this case. The majority made a textual argument. Gorsuch noted that the ADA defines “qualified individual” with present-tense verbs: a person who “can perform” a job that she “holds or desires.” According to the majority, this means the law only protects people who can do the job they hold or seek at the time they experience discrimination. If the discrimination occurs at a time when you are retired, as happened here, the ADA does not protect you. This interpretation of the law clearly harms retired people with disabilities.

The majority rejected the argument that their interpretation clashed with Congress’s intent to eradicate discrimination against people with disabilities. Justice Gorsuch wrote that “what Congress (possibly) expected matters much less than what it (certainly) enacted,” as discovered through his textualist approach to the law.

What did the dissent say?

Justice Jackson dissented, joined by Justice Sotomayor. She criticized the majority for “viewing this case through the distorted lens of pure textualism” and therefore denying retired people protections that Congress established in the ADA. She pointed out that Congress included the definition of a “qualified individual” simply to reaffirm that employers were not being required to fill jobs with people who could not actually do those jobs even with reasonable accommodations.

Jackson also pointed out that Stanley was still employed at the time the city adopted its discriminatory retirement policy. That made her a “qualified individual” under the ADA.

Jackson also made a direct attack on textualism. In a passage that Sotomayor did not join, Jackson wrote:

Our interpretative task is not to seek our own desired results (whatever they may be). And, indeed, it is precisely because of this solemn duty that, in my view, it is imperative that we interpret statutes consistent with all relevant indicia of what Congress wanted, as best we can ascertain its intent. A methodology that includes consideration of Congress’s aims does exactly that—and no more. By contrast, pure textualism’s refusal to try to understand the text of a statute in the larger context of what Congress sought to achieve turns the interpretive task into a potent weapon for advancing judicial policy preferences. By “finding” answers in ambiguous text, and not bothering to consider whether those answers align with other sources of statutory meaning, pure textualists can easily disguise their own preferences as “textual” inevitabilities

Jackson then made her meaning even plainer:

I think pure textualism is incessantly malleable—that’s its primary problem—and, indeed, it is certainly somehow always flexible enough to secure the majority’s desired outcome.

Jackson’s dissent reminds us of the importance of having fair judges who will make real the promises of laws and constitutional guarantees that advance liberty and justice.